Sustainable Design Is a Creative Opportunity, Not a Restriction

Isabelle Saxton is a sustainability strategist, clothing designer, and founder of the Global Sustainable Network consultancy, which focuses on integrating regenerative, circular, and sustainability strategies into fashion and textile business operations and creative individuals' lifestyles.

Due to her education at Harvard University and the Rhode Island School of Design, Isabelle prioritizes collaboration and holistic systems thinking while blending design expertise with deep knowledge of corporate sustainability, innovation, and environmental policy.

I interviewed Isabelle in the Conscious Fashion Collective Membership as part of our Member Spotlight interview series.

Below are some of the highlights from the conversation, including:

How sustainable design is a creative business opportunity,

Why true sustainability needs us to tackle lifestyle changes and business operations,

And how empathy can inform innovation in fashion.

What was the moment you knew you wanted to start the Global Sustainable Network?

Before the Global Sustainable Network came to be, I knew that I wanted to help other creatively-minded people become more sustainable. It was then through a series of conversations with people in the luxury and fast fashion industries that I realized there was a gap in the market for a mediary between supply chain and head office partners, highly tailored sustainability action plans for individuals and businesses, and sustainability strategies that take creative needs into account.

The actual moment, though, was when I was sitting across from a woman who was pre-interviewing me for an ESG role at a fast fashion start-up and — within five minutes — said, “Not to speak out of turn, but why don’t you start your own thing? Clearly you have the knowledge and resources to help more people outside of this role.” And I thought, “You know what, I think I do.”

Before you were a strategist, you were a designer. Can you tell us about how the ‘Impossible Dream’ jumper you created informed the journey you are on today?

Photography by Melissa Nyquist

I love the Impossible Dream jumper. It feels like a weighted blanket when you put it on. It’s local, naturally-dyed, organic Merino wool sewn up with secondhand cotton thread. It’s a mix of cautionary, frustrated, and thought-provoking statements and imagery with the aim of educating the viewer and raising their awareness about the unsustainability of the fashion industry — imploring them to reflect on the role they play.

The shape is inspired by a friend’s vintage tracksuit, and the name comes from a sign I saw on the street after shooting the collection. I hadn’t come up with a name that felt right, but I saw that and it worked so well.

My impossible dream was for everyone to be sustainable by choice. Not by guilt tripping people into thinking that it's the best thing to do — so they do it for five minutes and then stop — rather by educating them on the facts and allowing them to reconfigure their lifestyle to be more responsible socially and environmentally.

It’s a dream I’ve been working on for the last six years, and I think that’s why so many of Global Sustainable Network’s offerings are holistic and systems thinking-focused. I want to understand where people and businesses are so we can find a direction that will have lasting positive effects for generations.

How do your skills as a fashion designer inform the work you do today as a strategist?

I think with my design brain all the time. It helps to visualize problems and think of solutions from all angles, as well as engage with people in a collaborative and co-creating way.

I mainly work with fashion, textile, and lifestyle organizations. 80% of environmental impact can be avoided through design — so understanding how a designer thinks, knowing the creative restrictions they already have, and being able to come up with solutions that take the designer’s needs into account, helps to craft strategies that are long-lasting and impactful.

I also enjoy “translating” the designer’s needs to the business people’s needs and vice versa — almost using sustainability and circularity as a bridge between the two.

Do you have a personal definition of sustainability that you work from?

My definition of sustainability incorporates the three principles of the circular economy because I don’t think that we can live sustainably without a less wasteful and more regenerative lifestyle.

To me, sustainability is a dynamic system that encompasses the three interconnected sub-systems of human behavior, environmental, and industrial system dynamics. Sustainability works to improve the wellbeing of the interconnected system areas so that animate and inanimate life forms can flourish on Earth indefinitely.

The tools we can use to achieve this include designing and prioritizing options that reduce waste and pollution, maximize material value, and regenerate soil health, biodiversity, and ecosystems.

Developing your own definition of sustainability is important because it can then act as your North Star guide when making lifestyle and business decisions. So I encourage people and founders to come up with their definition of sustainability. Of course, your definition of sustainability should be grounded in scientific definitions, but adding your flair turns an abstract definition into a practical tool.

In saying all this, I do wish that there was a universally agreed-upon comprehensive definition of sustainability so that international policies and initiatives could be made with greater ease.

Can you describe one or two of your favourite projects you have worked on as a sustainability strategist?

They’re both tied by my love of researching and working with people.

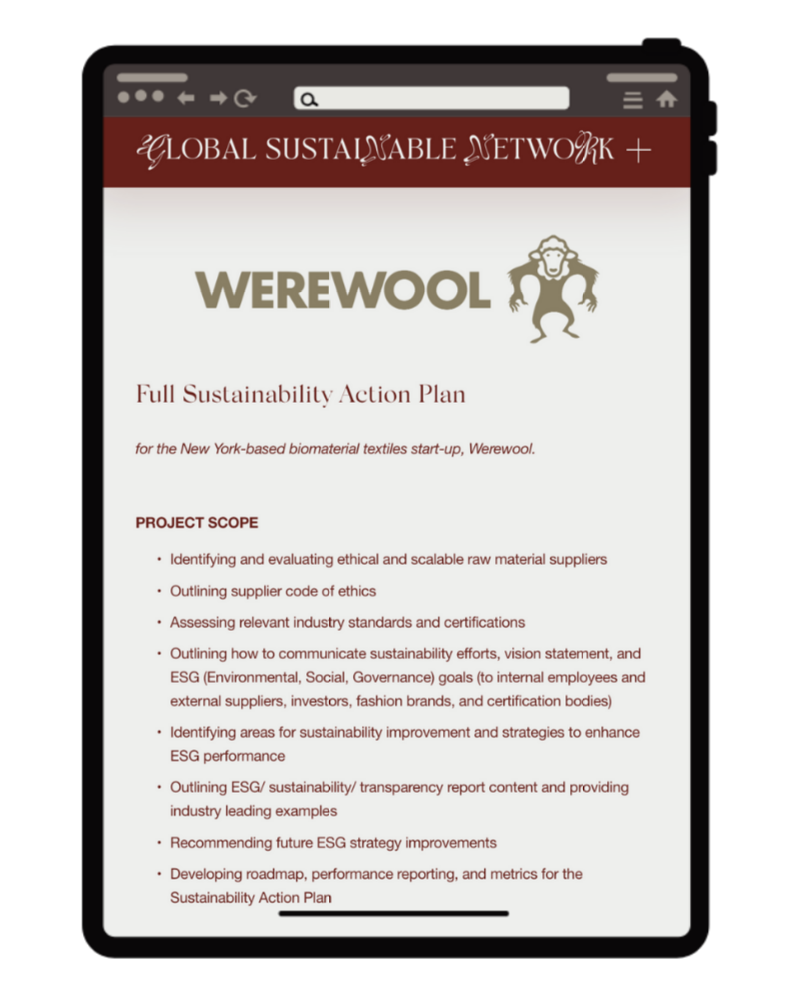

The one that inspired many of the services that I offer through Global Sustainable Network was a sustainability action plan for a startup biomaterial textiles producer in New York, called Werewool. I worked closely with the CEO and COO to understand the business’s needs and identify some strategy gaps. Then I came up with a roadmap that would help them find new suppliers, develop a supplier code of conduct, realign governance structuring, and transparently communicate sustainability progress despite not being able to share much due to the innovative nature of the product.

The other was in partnership with the North Carolina Textile Innovation and Sustainability Engine and two other consultancies. My role involved developing and incorporating sustainability, circularity, and regeneration materials, credible sources, and education into the materials for the new Fashion and Textiles curriculum for high schools across North Carolina.

I also worked on up-skilling four teachers on these topics and creating asynchronous educational materials for the 300 other teachers who will be teaching the curriculum, in some cases with no prior sustainability or circularity knowledge. The project will impact 25 000 students over its five-year lifespan, which is pretty epic too.

Many people see sustainability as a creative restriction. How do you push back at this to show people that sustainable design can be a creative opportunity?

I fell in love with the idea of sustainability being a creative opportunity when I kept hearing that it wasn’t possible or necessary to design with circularity or sustainability in mind because the industry isn’t sustainable or circular.

Being the harmonious contrarian that I am, I rebelled from the inherently wasteful, conventional fashion design process, which typically follows a process of: sketching the design, creating a pattern and prototype, buying the fabric and notions, cutting and sewing another prototype or the final product.

Instead I used to find secondhand materials, clothes, textiles, thread, and hardware on the street, in local shops, online, and through brands and acquaintances. When working with found materials, you can’t always easily follow the conventional fashion design process because the shape of the material will inform what you can create, which is a fun, creative challenge.

You find yourself asking: How can I use this material in a way that preserves its beauty, value, and quality while creating a uniquely designed garment? I often found that my favourite design pieces came from draping scrap materials on myself or a dress form.

My knitwear came to be because I wanted to create custom graphic T-shirts but I couldn’t find a sustainable way of printing back then. I realized that I could create bold imagery and text through machine knitting with naturally-dyed, organic, and local Merino wool.

Why is it important for you to tackle both individual lifestyle changes and business operations in your approach to integrating sustainability?

I’ve tackled both in my life. Once my mindset changed, when I was more informed on sustainability and circularity, that impacted how I make business decisions and how I interact with other businesses as a customer.

Also, people run businesses — so empowering the individual is important. If there’s a business out there that wants to become more sustainable, the people leading it likely have the desire or capacity to be more sustainable too.

Sustainability is an interconnected system with the three sub-systems of the human, industrial, and Earth. They all impact each other, whether we mean for them to or not.

Because businesses can be big and harmful, it’s easy to feel disempowered as an individual and slip into the mindset of, “Why does it matter if I buy or do this?” For example, buying a regenerative organic cotton T-shirt instead of a fast fashion conventional cotton T-shirt. But this small action helps to support much greater systems that can positively impact communities, ecosystems, and our health.

Regenerative organic farming prioritizes soil health and improving biodiversity so no synthetic or fossil fuel-based pesticides or fertilizers are used, tilling and mono-cropping are avoided, more water is naturally saved, significant amounts of carbon are stored, and some cotton buyers support local smallholder farmers and Indigenous communities. If the cotton is then spun, dyed using non-toxic, biodegradable inputs, assembled with organic thread and labels, then it can compost naturally instead of going to landfills, incinerators, or being dumped in nature. Whereas if it were conventionally dyed and sewn with synthetic, petroleum-based thread and labels, it would leach out toxic substances as it decomposes.

There are many examples like the t-shirt dilemma in the ways in which we live our lives. Those small mindset changes can add up to have a tremendously positive impact on ourselves, the local community, and the Earth.

Overall, adopting a sustainability, circularity, and regenerative mindset and living an aligned lifestyle has improved my life in many ways. So I want to help other people experience the immense appreciation for life that comes with this mindset shift.

One of your latest offerings is mapping scope 3 supply chain emissions. How can this add to a brand’s sustainability efforts?

When it comes to mapping greenhouse gas emissions, there are three main categories: scope one, two, and three. Scopes one and two look at your direct internal emissions and energy use. Scope three looks at everything else in your supply chain, from transport to fabric and clothing production.

Since scope three emissions can have an incredibly large breadth, they can be complex and hard to trace. Reporting isn’t mandatory for many brands, so most don’t report them. Yet, scope three emissions, on average, account for 80% of a business’s emissions.

I’ve always offered scope three screening, but my new offering ties in an interpersonal aspect, going into the supply chain to speak to the people on the ground and understand where emissions can be reduced in a way that takes into account key stakeholder needs and the workflow.

Mapping your scope three emissions can add to a brand’s sustainability because it’s highly quantitative, and depending on the methodology, can be extremely precise and tailored to your brand’s emissions without the need for using proxy data. So it’s a good way of seeing where more attention is needed to reduce inefficiencies and save energy, emissions, and waste — especially for fashion and textile brands.

Scope three allows you to compare the emissions of different fabric choices, transport, and suppliers. You can also sync it up with your finances pretty easily for full cost-benefit analyses.

Where do you suggest brands start when it comes to communicating their sustainability progress transparently and effectively?

I always recommend starting with defining sustainability. Ground it in scientific and industry-leading research, but come up with a statement that is uniquely yours. From here, it’s much easier to assess your operations, see what aligns with your definition, and what needs to change.

Then you can evaluate your pre-existing goals and strategies. You can see if you need to come up with new ambitions, which industry-leading certifications and standards could benefit your business. Once you have the backend in order, you’ll find that you have most of the data and content to put into a sustainability progress or transparency report.

Throughout this process, I highly recommend having a curious, agile, and interpersonal mindset. Change is tough but doing it as a team and taking into account your key stakeholders’ needs will pay off in the long run. I also have a free guide up on the Global Sustainable Network website that can help those on this communication journey.

Empathy is a big part of your ethos at Global Sustainable Network. How can empathy inform innovation in fashion?

I’ve noticed that people in the business world tend to shy away from language that can be seen as emotional or not grounded in fact. But empathy and tuning into someone else’s felt experience are vital to implementing local and industry-wide change.

Innovation is all about coming up with a solution to a problem that someone else hasn't been able to solve yet. So using empathy to understand what some of the biggest problems the fashion industry or the largest players face is key to finding an innovative solution. Conflict and tension don't often lead to long-lasting resolve, but truly understanding what a person or business faces can allow innovators to create a practical solution for a more sustainable, circular, and regenerative industry.

To connect with CFC Members and get featured in one of our Member Spotlights join the Conscious Fashion Collective Membership, the ecosystem for growing your sustainable fashion career and business. As a CFC Member, you can:

Connect with community and events,

Grow with industry workshops and resources

Gain visibility with showcase opportunities